Interesting Case July 2022

Case contributed by:

Bindu Challa MD, and Ashwini Kumar Esnakula MD

Department of Pathology, The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH

Have an interesting case to share?

Contact HPHS newsletter committee chair Sadhna.Dhingra@ProPath.com

Clinical history:

A G2P2 female in her late 20s presents as a transfer after precipitous delivery of a stillborn fetus at 36 weeks and 5 days of gestation. The patient complained of lower abdominal pain, yellowing of sclera, and lethargy for two days and was found to be hypoglycemic (45 mg/dl) on arrival.

Vitals are unremarkable except for Tachycardia 117 beats/min. Labs showed elevated total bilirubin – 11.8 mg/dl (normal range 0.0-1.2 mg/dl), elevated ALP – 592 IU/L (normal range 23-144 IU/L), low platelet count -54000 (normal range 150,000-400,000) elevated AST and ALT >300 IU/L(normal ranges AST – 0 to 55 IU/L and ALT- 0 to 60 IU/L) elevated PT, APTT, and INR, and low fibrinogen <60 mg/dl(normal range 200-400 mg/dl).Viral serologies and autoimmune studies were unremarkable. Serum Acetaminophen, amylase/lipase, alpha-1-anti-trypsin, and ceruloplasmin levels were normal.

She continued to worsen with hepatic encephalopathy over the next two days and subsequently underwent liver transplantation. The explanted liver was sent to pathology for examination.

Pathologic findings:

GROSS

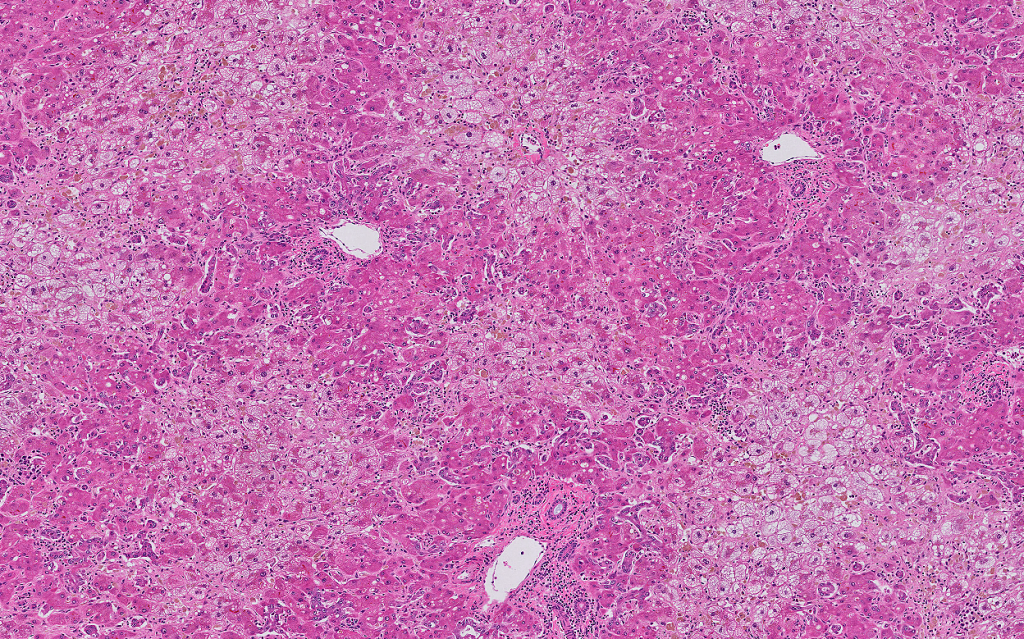

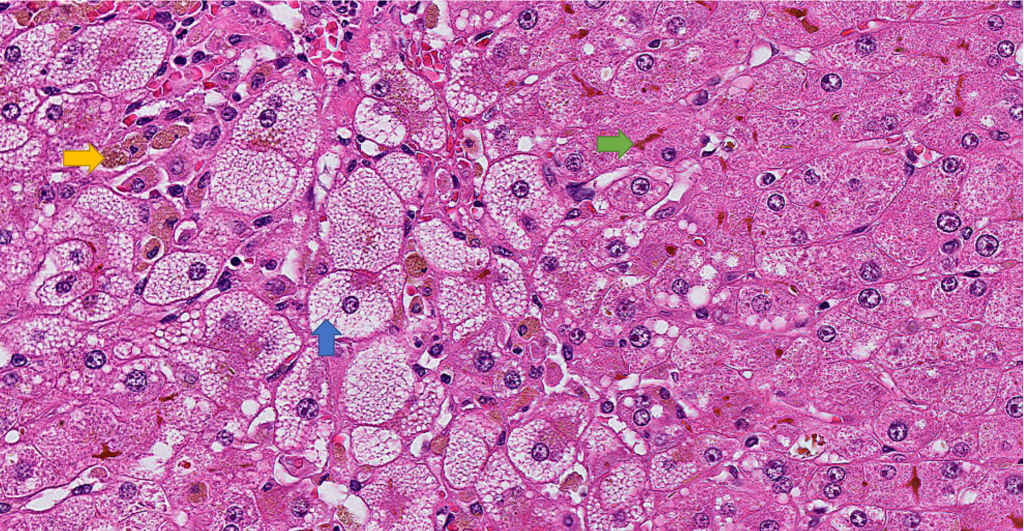

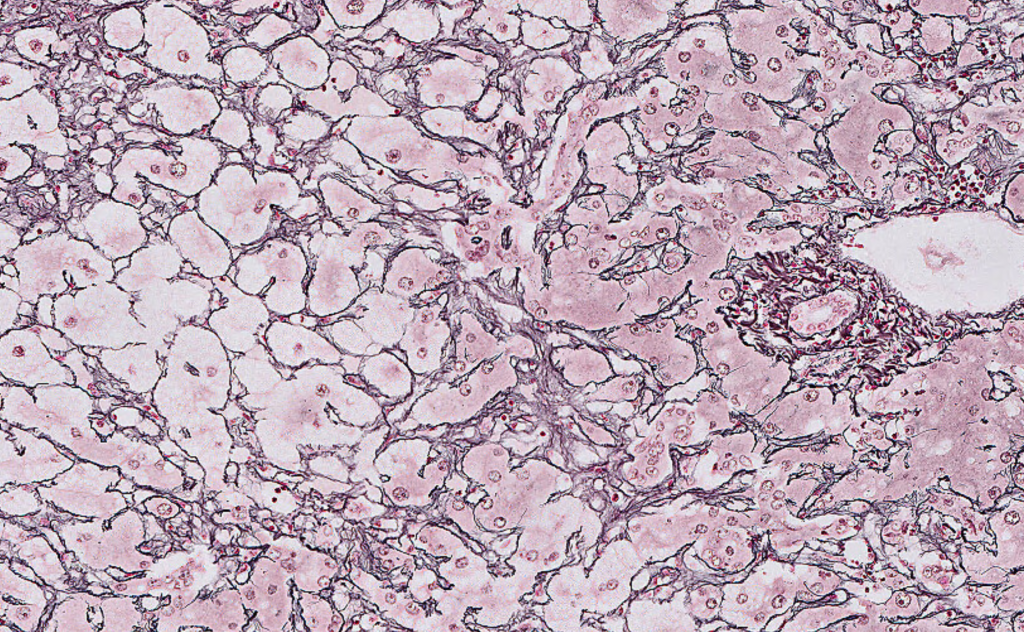

The sections of the explanted liver show prominent centrilobular microvesicular steatosis with sparing of the periportal hepatocytes. There is evidence of patchy hepatocyte dropout as evident by areas of reticulin framework collapse on the reticulin stain. There is patchy canalicular and hepatocellular cholestasis. Prominent sinusoidal Kupffer cell aggregates with ceroid-laden macrophages are noted. Rare foci of sinusoidal extramedullary hematopoiesis are noted. The periportal hepatocytes showed regenerative changes with prominent ductular reaction. Trichrome stain highlights prominent perisinusoidal fibrosis in the centrilobular region. There is no evidence of cirrhosis. PAS/D stain highlights prominent sinusoidal Kupffer cell aggregates in the centrilobular areas. There is no evidence of diagnostic intracytoplasmic globules. Iron stain is negative for hepatocellular iron deposition.

Overall, the explanted liver showed prominent centrilobular microvesicular steatosis with hepatocellular necrosis and dropout as evident by reticulin stain and reduced liver weight. These histologic findings are consistent with the clinical impression of acute fatty liver of pregnancy.

Diagnosis

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

Discussion

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) is a rare obstetric emergency that usually occurs in 3rd trimester but can be seen earlier in pregnancy as well as during the post-partum period. It is characterized by acute hepatic failure secondary to fatty infiltration of liver. Incidence is 1 in 7000 to 1 in 20000 deliveries. It is associated with high maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.

Pathogenesis is unclear. Deficiency in maternal-fetal fatty acid metabolism during pregnancy seems to play a role. 20% of the cases are associated with LCHAD (long-chain 3 hydroxyl CoA dehydrogenase) due to homozygous mutation resulting in fetal fatty acid defect leading to accumulation of metabolites in the maternal liver. Risk factors include multiple gestations, male fetuses, fatty acid oxidation disorders in fetuses, and previous episodes of AFLP.

Typical presenting symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting and can progress rapidly to liver failure, encephalopathy, coagulopathy, renal failure and respiratory failure. Laboratory abnormalities include elevated transaminases, hyperbilirubinemia, leukocytosis, elevated creatinine, thrombocytopenia, prolonged prothrombin time, hypo-fibrinogenemia, and hypoglycemia. Ulraosund of the liver may show non-specific changes, including fatty infiltration.

Clinically, AFLP and HELLP syndrome can have overlapping features and cause diagnostic difficulty. In HELLP, eclampsia, hemolysis (anemia), thrombocytopenia, and a mild increase in aminotransferases are seen. Histologically, the liver can show patchy or extensive necrosis, periportal hemorrhage, and fibrin deposition. In AFLP, pre-eclampsia is rare, and patients usually present with hypoglycemia, liver failure, and coagulopathy.

Liver biopsy is not necessary for the diagnosis of AFLP and carries a risk of bleeding due to coagulopathy (transjugular approach is preferred), although it is considered the gold standard for diagnosis. Liver biopsy is reserved for rare cases in which the diagnosis is in doubt and the results will affect patient care. Affected livers are grossly yellow and frequently are small, reflecting loss of parenchyma. The prominent histologic finding is microvesicular steatosis, usually in centrilobular (zone 3) areas but can also be diffuse. Microvesicular steatosis is characterized by small, bubbly cytoplasmic vacuolation with centrally located nuclei. Microvesicular steatosis is sensitive but not specific to AFLP. While acute viral hepatitis and drug-induced liver injury may, on occasion, lead to microvesicular steatosis, it does not approach the degree seen in AFLP or show a zonal distribution. Hyperplastic aggregates of Kupffer cells with lipofuscin can be commonly seen and related to hepatocyte necrosis and dropout. Canalicular and Hepatocellular cholestasis is commonly present. Extramedullary hematopoiesis may be present. Significant mononuclear infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes can be seen in portal tracts, lobules, and perivenular areas.

In patients who recovered from AFLP, microvesicular steatosis usually resolves quickly with reconstitution of normal hepatic lobular architecture and without the development of liver fibrosis.

Other histologic differential diagnoses include metabolic disease (Wolman disease/cholesteryl ester storage disorder due to lysosomal acid lipase deficiency), drug-related liver injury (tetracyclines, valproate, Reye syndrome), and toxins (alcoholic foamy degeneration).

Treatment consists of the delivery of fetus and supportive care, which usually results in rapid improvement. Recurrence of AFLP in subsequent pregnancies can occur. Although the theoretical recurrence risk in subsequent pregnancies is 25% with a mother carrying a homozygous mutant or compound heterozygous fetuses, it is uncommon and only a few cases have been documented. Liver transplantation is critical for a subset of patients who do not improve with pregnancy delivery.The true incidence of refractory acute liver failure from AFLP requiring liver transplantation is unknown, as are long-term outcomes after transplantation. In a study done on 39 patients with AFLP by Kushner et al, 8% patients died while waiting on transplant list, 17% had rejection and 22% had graft failure. Cumulative 5-year patient survival was similar and cumulative 5-year graft survival was lower in AFLP patients compared to other acute liver failure patients.

Given that early diagnosis and prompt treatment of AFLP are essential to maternal and fetal well-being, liver function tests must be measured in any pregnant woman past 22 to 24 weeks who presents with the aforementioned symptoms and signs. The patients can progress to acute liver failure necessitating liver transplantation.

Learning points:

- Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) is a rare obstetric emergency that usually occurs in 3rd trimester. It is characterized by acute hepatic failure secondary to fatty infiltration of the liver.

- The common histologic finding is microvesicular steatosis, usually in centrilobular (zone 3) areas but can also be diffuse. Other findings include portal, lobular and perivenular inflammatory infiltrates, hyperplastic aggregates of Kupffer cells containing lipofuscin, cholestasis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis.

- Differential diagnoses include HELLP syndrome, viral hepatitis, metabolic disease (Wolman disease/cholesteryl ester storage disorder due to lysosomal acid lipase deficiency), drug-related liver injury (tetracyclines, valproate, Reye syndrome) and toxins (alcoholic foamy degeneration).

- Delivery of fetus and supportive care usually result in rapid improvement. Liver transplantation is indicated in patients who progress to severe acute liver failure.

References:

- B. K. WJ, Odze and Goldblum Surgical Pathology of the GI Tract, Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas, Elsevier, Philadelphia, 3d ed edition, 2015.

- Rolfes DB, Ishak KG. Liver disease in pregnancy. Histopathology. 1986 Jun;10(6):555-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1986.tb02510.x. PMID: 3525371.

- Birkness-Gartman JE, Oshima K. Liver pathology in pregnancy. Pathol Int. 2021 Nov 24. doi: 10.1111/pin.13186. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34818440.

- Donck M, Vercruysse Y, Alexis A, Rozenberg S, Blaiberg S. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy – A short review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021 Apr;61(2):183-187. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13293. Epub 2020 Dec 31. PMID: 33382079.

- Vigil-De Gracia P. Acute fatty liver and HELLP syndrome: two distinct pregnancy disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001 Jun;73(3):215-20. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00364-2. PMID: 11376667.

- Liu J, Ghaziani TT, Wolf JL. Acute Fatty Liver Disease of Pregnancy: Updates in Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jun;112(6):838-846. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.54. Epub 2017 Mar 14. PMID: 28291236.

- Wei Q, Zhang L, Liu X. Clinical diagnosis and treatment of acute fatty liver of pregnancy: a literature review and 11 new cases. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010 Aug;36(4):751-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01242.x. PMID: 20666940.

- Rajasri AG, Srestha R, Mitchell J. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP)–an overview. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007 Apr;27(3):237-40. doi: 10.1080/01443610701194705. PMID: 17464801.

- Ibdah JA. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: an update on pathogenesis and clinical implications. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Dec 14;12(46):7397-404. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i46.7397. PMID: 17167825; PMCID: PMC4087582.

- Ko H, Yoshida EM. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006 Jan;20(1):25-30. doi: 10.1155/2006/638131. PMID: 16432556; PMCID: PMC2538964.

- Kushner T, Tholey D, Dodge J, Saberi B, Schiano T, Terrault N. Outcomes of liver transplantation for acute fatty liver disease of pregnancy. Am J Transplant. 2019 Jul;19(7):2101-2107. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15401. Epub 2019 May 16. PMID: 31017355.