Interesting Case July 2021

Case contributed by:

Kara Chan Phelps, MD and Suntrea Hammer, MD

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX

Have an interesting case to share?

Contact HPHS newsletter committee chair Sadhna.Dhingra@ProPath.com

Case history

A 59-year-old woman with Celiac disease and hyperlipidemia is referred for evaluation of chronically elevated liver enzymes, first noted 4 years previously. Her Celiac disease is well controlled with a gluten-free diet. Her medications include alendronate 70 mg daily, estradiol 0.5 mg daily, and progesterone 100 mg daily. She does not smoke nor drink alcohol. On physical examination, she is noted to be of short stature. She is 4’6” tall and weighs 45.9 kg; body mass index is 24.4 kg/m2.

Laboratory studies include: ALT 71 U/L, AST 61 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 229 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase 593 U/L, and total bilirubin 0.5 mg/dL. Viral hepatitis studies are negative. ANA is positive (1:320), while other autoimmune markers are negative. Serum levels of IgG, alpha-1-antitrypsin, and ceruloplasmin are within normal limits. Ultrasound imaging demonstrates unremarkable hepatic morphology and contour. A liver biopsy is performed.

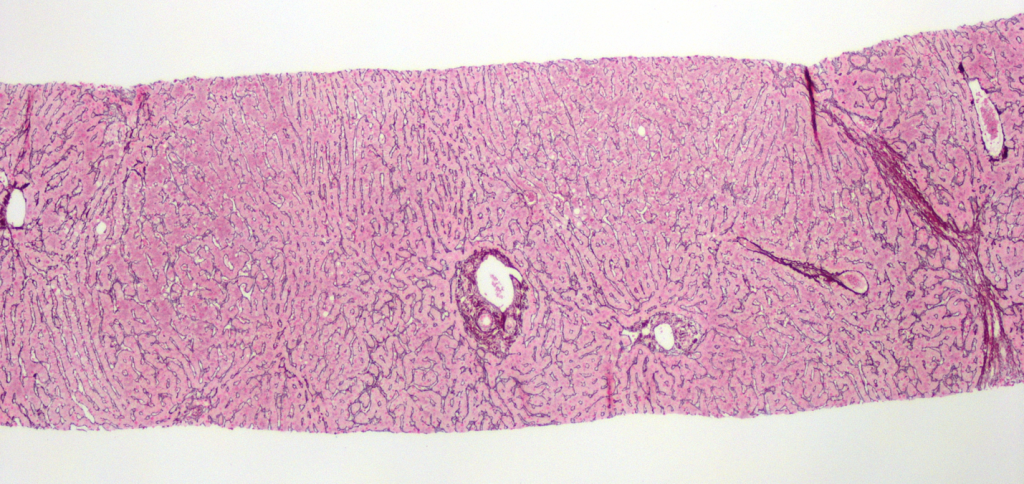

Figure 1. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia. Alternating bands of atrophic hepatocytes and hyperplastic-appearing hepatocytes impart a nodular appearance (reticulin, x40).

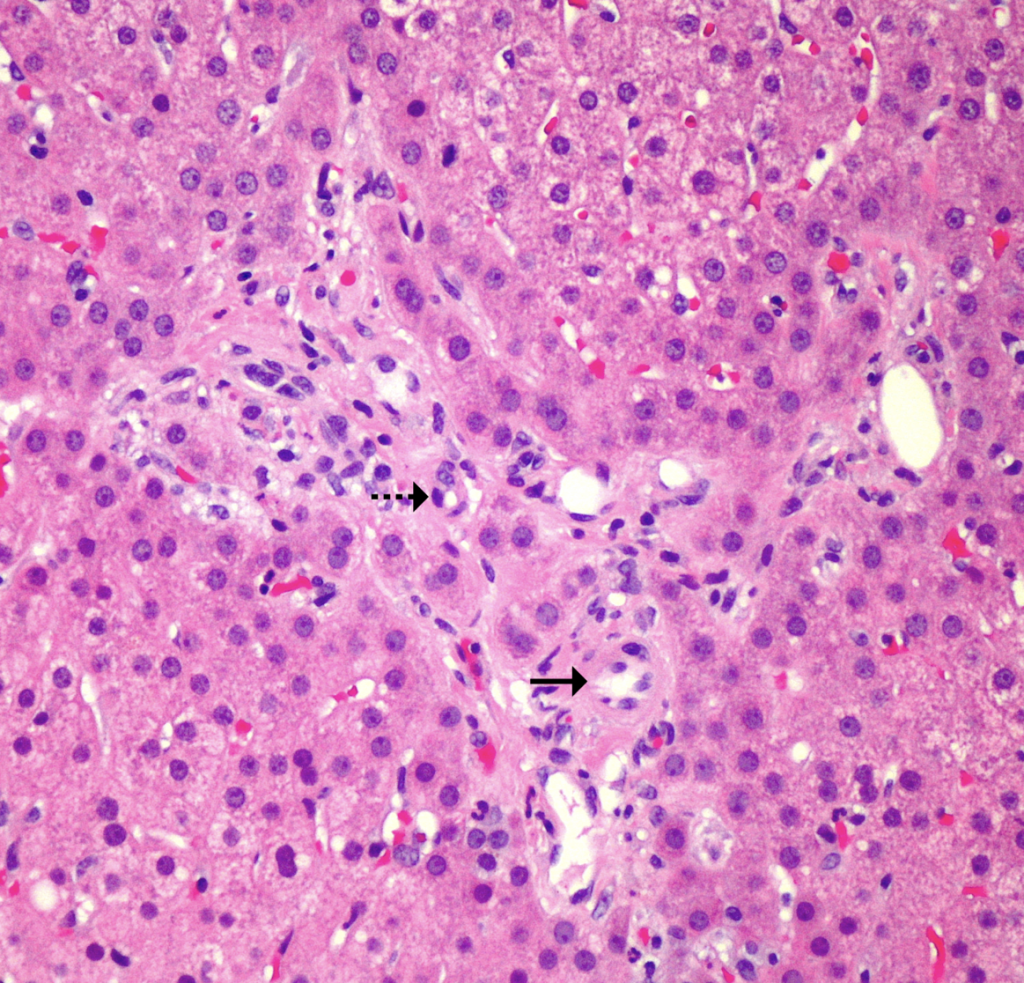

Figure 2. Obliterative portal venopathy. Portal tract with hepatic artery (→) and possible bile duct (⇢) but no centrally located portal vein. Small caliber vascular structures are present along the periphery of the portal tract (H&E, x200).

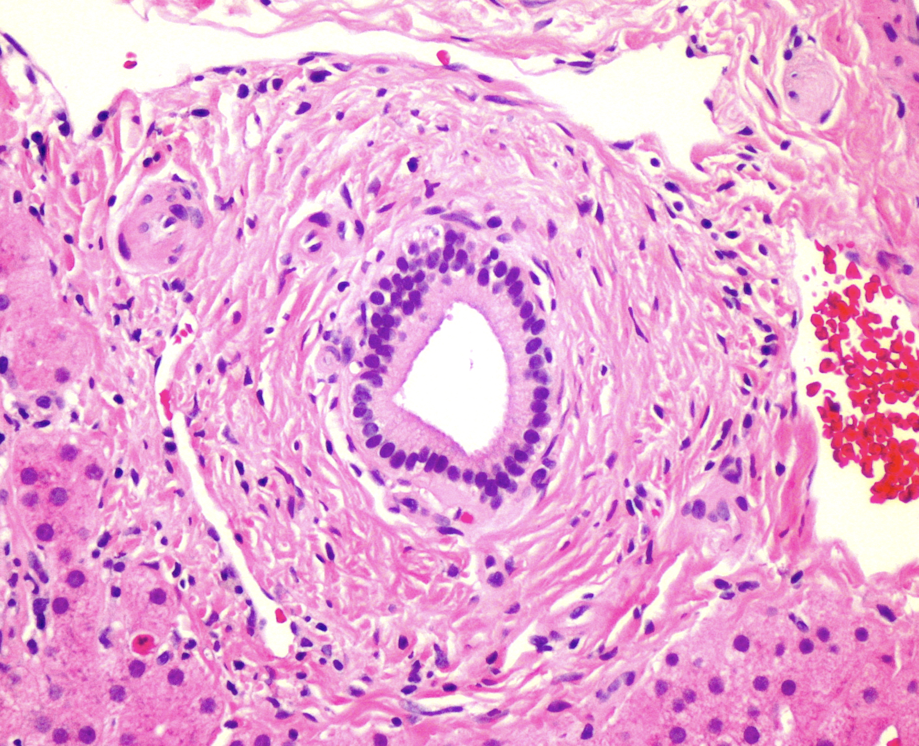

Figure 3. Concentric periductal fibrosis. (H&E, x200)

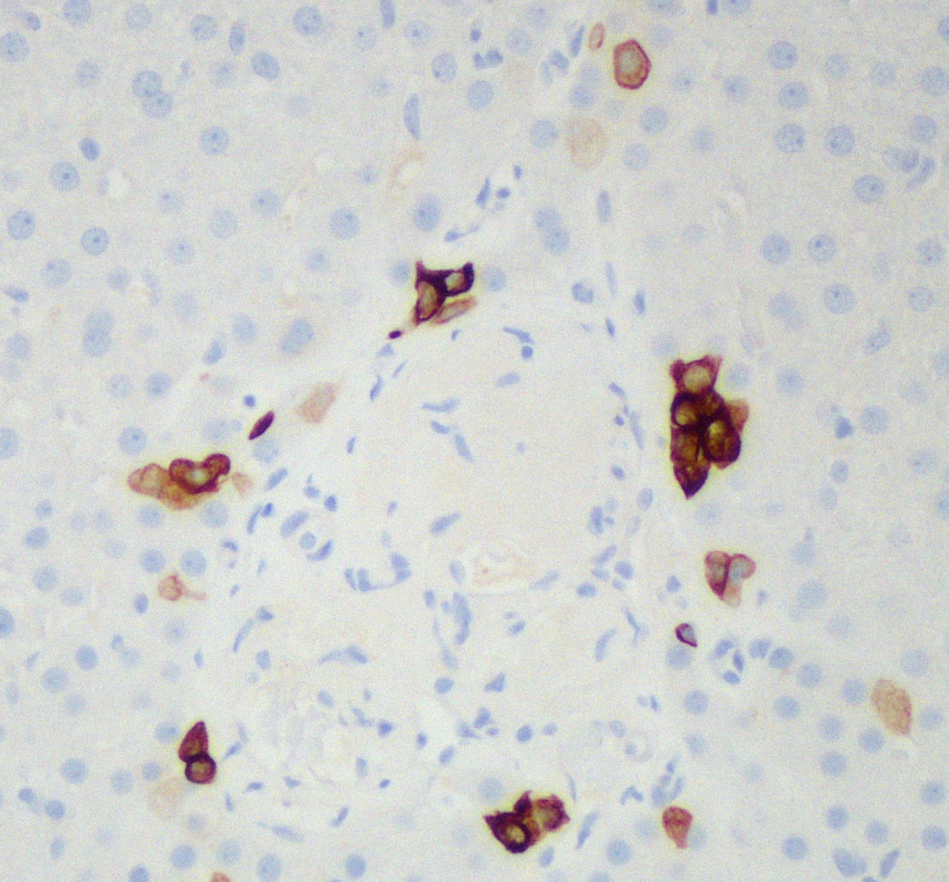

Figure 4. Ductopenia. CK7 highlights intermediate hepatocytes along the periphery of the portal tract, but no central native bile duct is seen (CK7, x200).

Pathologic findings

At low power, the liver has a vaguely nodular appearance due to alternating bands of atrophic hepatocytes and hyperplastic-appearing hepatocytes, consistent with nodular regenerative hyperplasia (Figure 1). Some of the portal tracts are fibrotic and many show structural abnormalities, including obliterative portal venopathy and concentric periductal (onion skin) fibrosis (Figures 2 and 3). Ductopenia is present, with mature bile ducts seen in only 11 of 23 portal tracts, confirmed with CK7 stain (Figure 4). There is no significant portal inflammation. The lobules show minimal macrovesicular steatosis (<5%) without ballooning degeneration. Trichrome stain demonstrates portal and bridging fibrosis.

Diagnosis

Liver involvement by Turner syndrome

Discussion

A review of the electronic medical record reveals that the patient has Turner syndrome. Caused by partial or complete loss of one of the X chromosomes, Turner syndrome affects approximately 1 in 2500 females, making it the most common genetic disorder in females.1,2 Phenotypic manifestations include short stature, webbed neck, congenital lymphedema, coarctation of the aorta, and gonadal dysgenesis.2 Abnormalities in liver tests are a frequent finding in patients with Turner syndrome, with one study of middle-aged patients reporting elevated liver enzymes in “more than 80 percent” of participants.3

Three main patterns of liver involvement have been described in Turner syndrome: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, architectural changes, and biliary lesions. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, encompassing simple steatosis and steatohepatitis, is the most common finding.4 As obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome are frequent in patients with Turner syndrome,2,5 this pattern is likely driven by the same factors as in the general population. Architectural abnormalities include nodular regenerative hyperplasia, obliterative portal venopathy, and multiple foci of focal nodular hyperplasia; these architectural changes may result from congenitally abnormal vessels.4,6 Biliary lesions include ductopenia and concentric periductal fibrosis of intrahepatic bile ducts, resembling small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis; alterations in blood supply may also underlie these changes.1,4,6 Cirrhosis is reportedly five times more likely in patients with Turner syndrome.5

Gonadal dysgenesis, one of the characteristic features of Turner syndrome, is managed with hormone-replacement therapy.2 Estrogen therapy has not been definitively implicated in the liver alterations in Turner syndrome, and current evidence suggests that hormone replacement does not need to be discontinued in patients with liver involvement. Patients with biliary lesions may benefit from treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid.4,6

In this patient, the differential diagnosis included Celiac hepatitis, as abnormal liver tests are also common in patients with Celiac disease. Histological changes are typically mild or nonspecific, with portal and lobular mononuclear inflammation being the most common findings. As injury is gluten-dependent, laboratory and histologic alterations typically resolve with strict adherence to a gluten-free diet. However, primary biliary cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis occur in higher rates in patients with Celiac disease, so liver biopsy should be considered in patients with persistent liver abnormalities.7

Learning points:

- Patients with Turner syndrome frequently show abnormalities in laboratory liver tests.

- Patterns of liver involvement in Turner syndrome include non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, architectural abnormalities, and biliary lesions.

- Architectural changes include nodular regenerative hyperplasia, obliterative portal venopathy, and multiple focal nodular hyperplasia.

- Biliary lesions include ductopenia and concentric periductal (onion skin) fibrosis.

References

- Valentini P, Angelone DF, Rossodivita A, Francalanci P, Buonsenso D, Ceccarelli M, Callea F. Ductopenia and fetal liver-like architecture as unique and evocative sign of Turner syndrome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013 Apr;17(8):1132-8. PMID: 23661530.

- Sybert VP, McCauley E. Turner’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 16;351(12):1227-38.

- Sylvén L, Hagenfeldt K, Bröndum-Nielsen K, von Schoultz B. Middle-aged women with Turner’s syndrome. Medical status, hormonal treatment and social life. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1991 Oct;125(4):359-65.

- Roulot D. Liver involvement in Turner syndrome. Liver Int. 2013 Jan;33(1):24-30.

- Gravholt CH, Juul S, Naeraa RW, Hansen J. Morbidity in Turner syndrome. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998 Feb;51(2):147-58.

- Roulot D, Degott C, Chazouillères O, Oberti F, Calès P, Carbonell N, Benferhat S, Bresson-Hadni S, Valla D. Vascular involvement of the liver in Turner’s syndrome. Hepatology. 2004 Jan;39(1):239-47.

- Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. Liver involvement in celiac disease. Minerva Med. 2008;99(6):595-604.