Interesting Case January 2016

Clinical History

A 51 years old woman was referred for liver transplantation on account of end-stage primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC). She had presented with variceal bleeding outside. Her liver was found to be enlarged but she had normal INR and albumin although bilirubin was slightly elevated at 1.8 mg/dL (31 μmol/L). She however had other features of portal hypertension including splenomegaly and low platelets (78,000/µL). Serologically she was AMA positive (high titer), IgM was elevated but IgG and IgA were normal. Liver enzymes were AST 12 U/L, ALT 10 U/L, and ALP 200 U/L (on Urso treatment). Ultrasound confirmed nodular and cirrhotic liver. She was listed for transplantation as end-stage PBC.

She successfully underwent living related liver transplantation. The explanted liver weighed 1233 gm and appeared vaguely nodular but not cirrhotic. Cut sections revealed no mass lesions. Micrographs from the explanted liver are shown.

Liver Explant Microscopic Findings

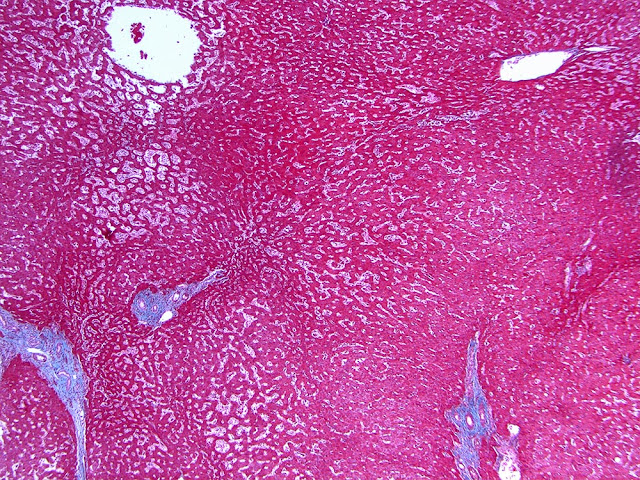

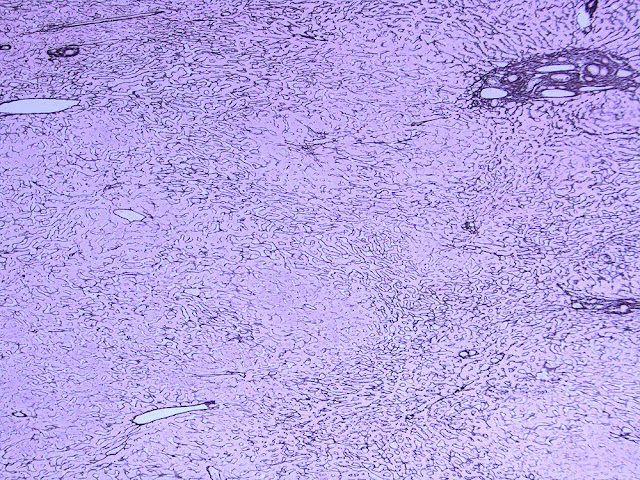

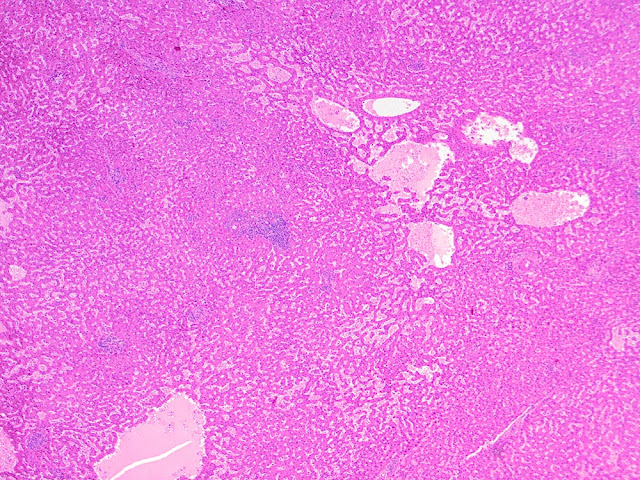

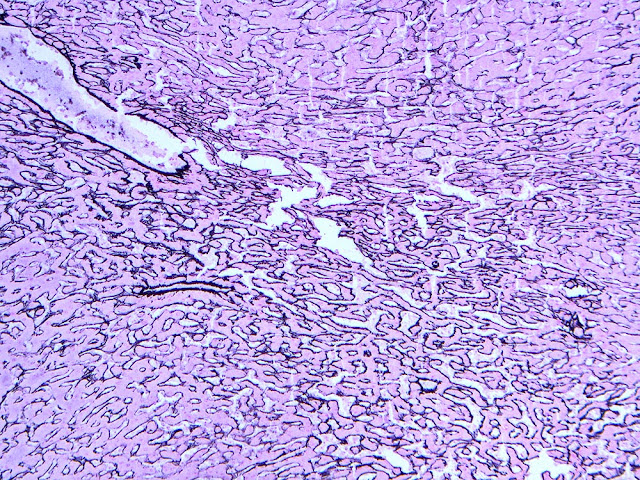

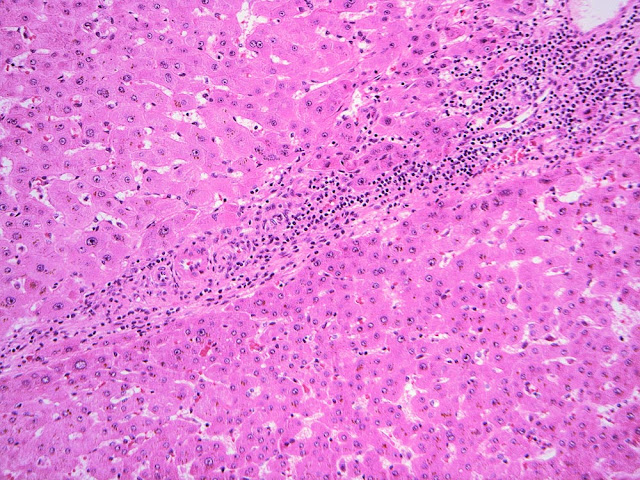

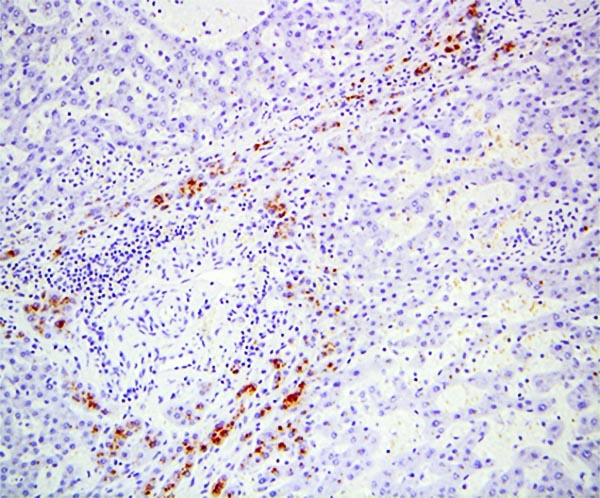

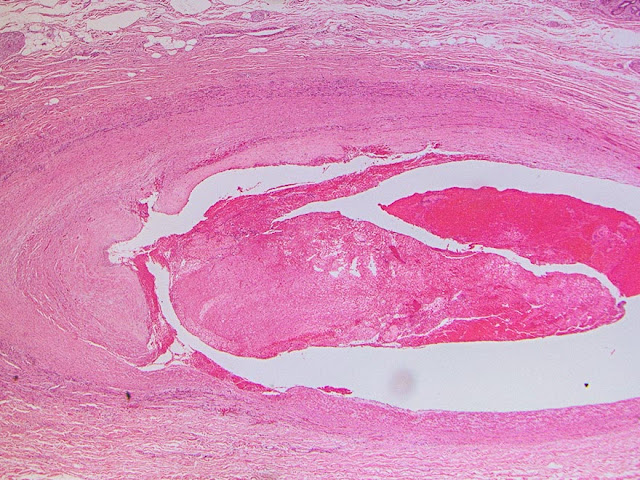

The explant showed a nodular liver with areas of sinusoidal dilatation, and occasional incomplete septae, but no evidence of cirrhosis. Rare florid ducts of PBC are present but there is mild ductopenia that came down to approximately just 20% of the terminal bile ducts; the larger bile ducts appear normal as are most of the small/terminal bile ducts. Several small portal tracts however have increased portal and occasionally periportal fibrosis and no visible portal veins. The larger portal tracts often have small portal veins when compared with the corresponding hepatic artery or bile duct, with thickening of the veins walls (obliterative portal venopathy). Reticulin stain demonstrates nodularity not bordered by fibrous septae, the edge of the nodules having compressed reticulin fibers (NRH). Sections from the hilum demonstrate major but non-occlusive portal vein thrombus.

Diagnosis

Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension from a combination of nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH), portal vein thrombosis, and obliterative portal venopathy (OPV) in a patient transplanted for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis

Major Learning Points

- Portal hypertension in patients with normal liver function (albumin, bilirubin, INR) should raise the possibility of non-cirrhotic cause.

- Primary biliary cirrhosis and other chronic biliary diseases could cause portal hypertension from NRH and/or obliterative portal venopathy without being cirrhotic or “end-stage”.

- Liver explant examination is important to verify cause of liver disease as this has a significant implication on post-transplant course and management.

Discussion

Portal hypertension is a common end-stage presentation of many chronic liver diseases the likelihood of which parallels severity of cirrhosis. As such patients with Childs-Pugh C cirrhosis have worse manifestations of liver failure from cirrhosis than Childs-Pugh A and B patients. Symptomatic cirrhosis is typically accompanied by abnormal liver function tests (albumin, INR/coagulation parameters, and bilirubin) although liver enzymes could remain normal or near normal even in advanced cirrhotics. Portal hypertension with normal liver function could occur in compensated cirrhosis but normal function accompanied by symptoms of portal hypertension like variceal bleeding in this patient, should raise the possibility that portal hypertension may not be arising from cirrhosis. This is because decompensated cirrhosis is a reflection of failing ability of liver parenchyma to optimally function. Whereas most (not all) cases of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension with normal hepatic mass are less likely to manifest as functional abnormality. In such cases features of PH are limited to vascular shuntings (varices and sometimes encephalopathy) and splenomegaly (including low platelets).

Also liver vasculature could be secondarily affected by chronic biliary diseases as exemplified by this case. For this reason, and for several years, PBC for example has been recognized as a cause of NRH and associated with OPV. It has been postulated that repeated pre-sinusoidal injury possibly from PBC-associated portal inflammation could secondarily cause inflammation and loss of small portal veins over time, leading to NRH. [Kew MC, et al. Gut. 1971;12(10):830-4]. In this case and possibly in combination with other factors, the direct effect of chronic portal vein injury is also manifested as obliterative portal venopathy, OPV.

OPV, (also called hepato-portal sclerosis, HPS), is an entity in which portal hypertension resulted from injury to and thickening of the wall of large and intermediate intrahepatic portal veins and obliteration of the smaller veins (Nayak NC & Ramalingaswami V. Arch Pathol 1969; 87: 359-69; Aggarwal S et al. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58: 2767-76.). It could complicate a long list of diseases including PBC as well as many systemic and organ-specific immunologic diseases (Lee H, Rehman AU, Fiel MI 2015 J Pathol Transl Med Epub ahead of print), for which reason an immunologic basis has been proposed. Another association with the OPV is thrombophilia (Hillaire S, et al. Gut 2002; 51: 275), with some OPV patients secondarily developing secondary portal vein thrombosis, also seen in the present case.

It would therefore appear that the findings in the presented case are part the same process that started with vascular (portal vein) injury in the context of PBC leading to OPV, which in turn gave rise to NRH (Wanless IR, et al. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980; 59: 367-79.); and ultimately portal hypertension. The development of large portal vein thrombosis could be from portal hypertension since this patient has so far not been found to have a thrombophilic state. She is now 3 years post-transplant and doing excellently well.

Case contributed by:

Oyedele Adeyi, M.D.

University of Toronto

References:

- Abraham SC, Kamath PS, Eghtesad B, Demetris AJ, Krasinskas AM. Liver transplantation in precirrhotic biliary tract disease: Portal hypertension is frequently associated with nodular regenerative hyperplasia and obliterative portal venopathy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(11):1454-61

- Kew MC, Varma RR, Dos Santos HA, Scheuer PJ, Sherlock S. Portal hypertension in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut. 1971;12(10):830-4

- Nayak NC, Ramalingaswami V. Obliterative portal venopathy of the liver: associated with so-called idiopathic portal hypertension or tropical splenomegaly. Arch Pathol 1969; 87: 359-69.

- Aggarwal S, Fiel MI, Schiano TD. Obliterative portal venopathy: a clinical and histopathological review. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58: 2767-76.

- Lee H, Rehman AU, Fiel MI. Idiopathic Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension: An Appraisal. J Pathol Transl Med. 2015 Nov [Epub ahead of print]

- Hillaire S, Bonte E, Denninger MH, et al. Idiopathic non-cirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension in the West: a re-evaluation in 28 patients. Gut 2002; 51: 275-80.

- Wanless IR, Godwin TA, Allen F, Feder A. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver in hematologic disorders: a possible response to obliterative portal venopathy. A morphometric study of nine cases with an hypothesis on the pathogenesis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980; 59: 367-79.