Case History:

A 47 year old man with a past medical history of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity presented with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and lower extremity swelling. A multiphase MRI of the liver revealed multiple calcified and non-calcified hypoenhancing masses, more confluent in, and involving most of, the right hepatic lobe. Smaller discrete lesions were seen in the left lobe, measuring up to 4.1 cm. The right portal vein showed findings suspicious for tumor thrombus. Needle-core biopsies were performed.

|

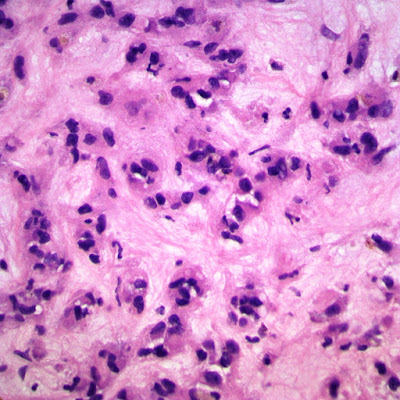

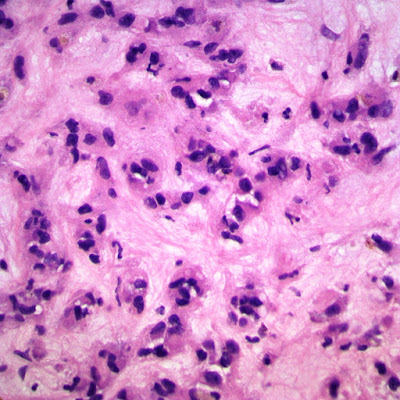

| Figure 1: 4x, 1st biopsy core. |

|

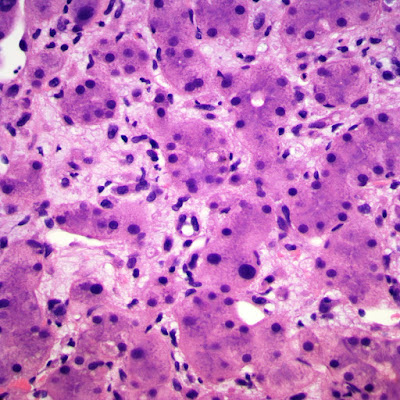

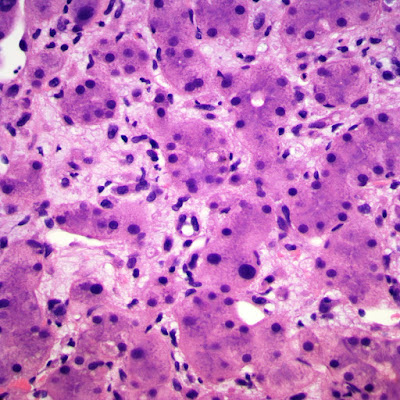

| Figure 2: 10x, 1st biopsy core. |

|

| Figure 3: 20x, 1st biopsy core. |

|

| Figure 4: 40x, 1st biopsy core. |

|

| Figure 5: 40x, 1st biopsy core. |

|

| Figure 6: CD34, 1st biopsy core. |

|

| Figure 7: 10x, 2nd biopsy core. |

|

| Figure 8: 40x, 2nd biopsy core. |

|

| Figure 9: CD34, 2nd biopsy core. |

|

| Figure 10: CD34, 2nd biopsy core. |

In addition to the CD34 immunohistochemistry (IHC) stain shown, the lesional cells were positive for CD31 and Factor VIII.

Diagnosis:

Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma

Discussion:

Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma (EHE) is a rare, low grade vascular malignancy that was first recognized as a distinct clinicopathologic entity in the early 1980s in the soft tissues and lung. In the latter organ it was originally referred to as intravascular bronchioloalveolar tumor (IVBAT). It is now known to occur in many sites, including the liver.

Its histologic features are quite distinctive in the liver. In hepatic EHE the tumor is often multifocal, with calcifications seen radiographically. They are firm, white to yellow, with ill-defined borders. Tumor cells are both dendritic and epithelioid in various proportions. The spindle cells are irregularly shaped and elongated. Epithelioid cells are rounder with more abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Small papillations or tufts of tumor cells may be seen within thin-walled vascular spaces. Abortive vascular differentiation is typically seen, with tumor cell cytoplasm containing a single vacuole representing a capillary luminal space — so-called “blister cells.” Tumor cells lie within a variably myxoid to fibrous stroma. The tumor often infiltrates hepatic vein and portal vein branches, leading to Budd-Chiari syndrome as a possible presentation. The tumor tends to grow around and leave pre-existing hepatic structures intact, particularly at the periphery of tumor nodules. In these areas, only subtle infiltration of tumor cells may be seen within sinusoids, in an otherwise architecturally normal liver, something which can be particularly treacherous in small liver biopsies.

On core biopsy material, the differential diagnosis can be separated into two distinct categories:

- the lesion is clearly neoplastic but the histogenesis of the tumor is not obvious

- fibrosis vs. EHE.

In the first setting, the lesion is sufficiently cellular and atypical to be clearly neoplastic, and the differential diagnosis often includes carcinomas such as hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, or metastatic carcinoma. IHC stains for vascular markers (CD34, CD31, Factor VIII, FLI1), are typically positive in EHEs and negative in carcinomas. Patchy keratin staining can be seen in some tumor cells of EHE, or in entrapped hepatocytes or bile ducts, and care should be taken not to misdiagnose a carcinoma.

In the second setting, the tumor is hypocellular and has a fibrotic stroma, and can closely mimic fibrosis or confluent necrosis with drop-out. In this setting, the tumor can be very difficult to diagnose on limited core biopsy material. One can look for focal areas of greater cytologic atypia, or areas of sinusoidal infiltration of tumor cells. A vascular IHC stain can be helpful to highlight such infiltration, keeping in mind not to misinterpret capillarization of sinusoids, which can be seen in various settings.

The largest series on hepatic EHE is from the AFIP, in which 137 cases were described. It typically occurs in middle-aged adults (though rare cases in children have been reported), with a slight female predominance. It presents with non-specific symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, hepatosplenomegaly, or as Budd-Chiari syndrome, or as an incidental finding. It is slowly progressive and treated with excision, or transplantation in advanced cases. In this presented case, the patient was immediately referred for liver transplantation. Because the tumor grows so slowly, transplantation can still be performed in the presence of extra-hepatic disease. Overall 5-year survival rate is 43-55%.

More recently, a characteristic translocation has been reported: t(1;3)(p36.3;q25), resulting in a WWTR1-CAMTA1 fusion. This translocation has been shown to occur in the majority of EHEs of various sites, and not in their histologic mimics. A smaller subset of EHEs show a YAP1-TFE3 fusion. A recent study showed a high sensitivity and specificity for a CAMTA1 IHC stain, suggesting its possible utility as a diagnostic marker.

References

Antonescu CR, et al. Novel YAP1-TFE3 fusion defines a distinct subset of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2013; 52: 775-784.

Errani C, et al. A Novel WWTR1-CAMTA1 Gene Fusion is a Consistent Abnormality in Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma of Different Anatomic Sites. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2011; 50: 644-653.

Makhlouf HR, Ishak KG, Goodman ZD. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of the liver: a clinicopathologic study of 137 cases. Cancer 1999; 85: 562-582.

Mehrabi A, et al. Primary malignant hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a comprehensive review of the literature with emphasis on surgical therapy. Cancer 2006; 107: 2108-2121.

Shibuya R, et al. CAMTA1 is a useful immunohistochemical marker for diagnosing epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Histopathology 2015 Apr; doi 10.1111/his.12713.

Contributed by:

Nafis Shafizadeh, MD

Southern California Permanente Medical Group

Woodland Hills Medical Center